A training on the social dimension of agroecology

Chapter authored by by F. Gillet and M. Terzo, Haute Ecole de Bruxelles, Belgium

Introduction

Agroecology is in the same time a large panel of techniques (local agriculture, organic-agriculture, permaculture, resilient agriculture ….), a critical look on those techniques with a theoretical reflexion on political, economical, cultural, social, ecological, human … levels and at the end also a philosophy that could be simply summarized as “an art of connecting and balancing agricultural activities and their ecological dimension in the everyday life”.

An important need of agroecology is to connect people together because they have to get out of the industrial and productive paradigm organised only on a managerial perspective. A possible alternative is thus cooperation between partners at the different levels of a more local, organic, resilient system. Cooperation means that people know each other better that only through money and business exchanges. They develop trust based on real relations, at least on the agricultural level but most of the time also in the everyday life and in the conscience of the common good.

We‘ll see in this training two dimensions of agroecology, the urban and the rural ones.

The training starts with a rural experience, by living in a farm that is today an ecovillage where agroecological dimension is present through vegetables production, goats milk production, organic bakery, organic food selling … but where a community of 40 people is also living and sharing a large space where several apartments or houses were built in addition to the original farm building. The aim is to reflect how agroecology fits in those several professional activities, how the common life is organized and what the interactions between both professional and common lives are. This is a first approach of the social dimension.

The second part of the training takes place in Brussels by visiting several projects. The urban farm called “Nos Pilifs” is a social economy enterprise employing workers with disabilities. Another urban farm in the city of Evere welcomes young workers for a practice placement of six months allowing them to learn the first steps of organic-agriculture. The district of Haren (North of Brussels) is another place where a tradition of urban gardening exists for one century. We there encounter activists (patatist movement) living on a place in Haren where a project of building a mega-prison is a real danger for maintaining this urban gardening tradition.

A TTT (training the trainers) day takes place at the end of the training. This day aims to see how the participants learned through the proposed activities and visits and how to have a reflection on the several methodologies used.

This document “social dimension of agroecology” aims to inform you about how this training happened, proposing you different tools allowing to organize such a training or a part of it in another context where it could be useful.

1.1 What is agroecology?

Formerly, agroecology is a new way of rethinking agricultural practices trough the knowledge of ecology (Altieri 1987). Here raise several other questions: what is ecology, why and how should we integrate its principles to the conventional agriculture?

Ecology is the scientific analysis and study of interactions among organisms and their environment, such as the interactions organisms have with each other and with their abiotic (soil, water, climate...) environment1. But since the Green Revolution, to increase agricultural productions, men constantly tried to overcome the constraints imposed by the natural environment. They changed the soil structure by the tillage and mechanization, and the soil composition by adding fertilizers, lime, pesticides... These changes have killed the natural macro and microbial life of the soil or they drastically disrupted the balance between these living organisms. They also conduct to global soil erosion. Fields are nowadays strictly artificial areas disconnected from their surrounding (semi-)natural environment. These fields even act on the environment as a trap where animals or plants which fall into it eventually die there.

According to the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA 2005), it is now assumed that the global food system is a major source of land, forests, fish stocks, biodiversity and water degradation with most of the ecosystem services degraded or unsustainably managed2. These ecosystem services are the benefits people obtain from ecosystems. They include supporting services such as nutrient recycling, primary production and soil formation ; provisioning services of wild food, water, biomass, medicinal resources, natural fertilizer… ; regulating services such as climate regulation, air and water cleaning, waste decomposition… ; and cultural services for sciences, education, ecotourism, wellness, leisure activities, and even spiritual experiences.

For instance, the use of insecticides to protect crops from pests also kills their pollinators (Potts et al., 2010). Reducing diversity and abundance of pollinators not only decreases the crop production (Kevan & Phillips 2001) but also affects the reproduction of insect-pollinated wild plants (Biesmeijer et al. 2006). This loss of wild plant biodiversity then affects the abundance and biodiversity of their pollinators, and thereby decreases the crop production. But the use of insecticides is not the only cause of disappearance of pollinators. Because of the massive use of chemical fertilizers in the fields, the nitrogen cycle is disrupted and the amount of available nitrogen for plants is 20 to 40 higher than the natural fallout, even in semi-natural areas. This large amount of nitrogen favours grasses, which are wind-pollinated plants, to the detriment of entomophilous plants that feed pollinators. The almond trees orchards in the US are an extreme example of this vicious circle. Their 130,000 hectares of almond trees cultivated in California now require the rent of 2 million honey bee hives in February to supply to lose of the wild bees (Summer & Boriss 2006).

As seen from this example, conventional farming techniques do not only affect the biodiversity of cultivated land, but also the whole environment, even to the detriment of the services that this environment can provide to the farmers.

The loss of biodiversity and soil erosion is not the only threat that conventional agriculture places on us. It is also engaged in the climate change and the energy crisis. For instance, the intensive rearing of cattle produce a significant amount of methane, a gas involved in the greenhouse effect leading to the global warming. And the production of one tone of nitrogen fertilizer requires a ton of oil equivalent.

One could also mentions the groundwater pollution by nitrates or the public health problems caused by pesticides widely used on fruits and vegetables or by the use of antibiotics required by intensive breeding.

After why, let see now how agroecology can offer an alternative.

Agroecology is based on a set of principles that involve different methods and techniques and that operate at three levels. These principles are summarised and completed by Stassard and collaborators (Stassard et al., 2012). They all challenge the productivity-narrative, based on biotechnology, for a sufficiency narrative based on agroecology. The three levels are: the production system in the strict sense, the food system in a broader sense, and the relationship between food production and society as a whole. At those three levels, agroecology promotes alternatives for a sustainable farming that is more independent, more self-sufficient, and so more resilient.

At the production system level, Gliessman (1998) suggest to exceed the scale of the cultivated plot to take an interest in the whole farming system. In line with this idea, Perfecto & Vandermeer (2010) suggest an integrated management of biodiversity with food production, making the farmer a land sharing rather than a land sparing manager. These ideas led to what is now called the integrated farming3 for a more sustainable farming.

At the cultivated plot scale, agroecology aims to drastically reduce the amounts of non-renewable external inputs and tillage techniques, which are cause of soil degradation. Chemical fertilizers can be replaced by natural fertilizers (manure, compost, leguminous crops, green manures). Chemical pesticide can be replaced by biological pest control. Field margins can be created to sustain wildlife and so revive part of the natural ecosystem services (pollination, pest control by natural parasites and predators as birds, natural barriers against wind and water erosion...). Winter planting stores the fertilizer surpluses, protects the soil from erosion and leaching, protects the soil microflora and microfauna during the winter and promotes the growth of spring planting by releasing fertilizers and by aerating and structuring the soil. Thanks to zero tillage seeding, the structure and wild life of the soil is preserved. All those techniques lead to the organic farming.

At a larger scale, farmers can also sustain biological synergies that promote the ecosystem services by increasing the genetic diversity, the species varieties, in time and space. These synergies should take place not only inside the farming system but also with its surrounding environment.

The principles of agroecology also consist in a global reduction of energy use, especially the use of petrol to favour renewable sources of energy such as wind, solar, water or biomass energy, the parsimonious use of water and the reduction of waste production (e.g. biomass recycling).

Finally, while each of the methods and principles mentioned here can be applied in conventional farming, agroecology exists only through their combined application.

At the second level, agroecology also deals with the “food system” because the current industrial model of food production and distribution is no more sustainable. This larger food system scale takes into account the spinneret and consumer organization dimensions, and the socio-economic and political dimensions of the construction of food systems (Francis et al., 2003). The principles of sustainability and self-sufficiency mentioned above are now applied to the distribution and marketing of food. New spinnerets appear, promoting local and seasonal foods, peasant, organic and urban farming. Consumers are organised in joint and solidarity purchasing groups to sustain local farmers. Some stores offer foods in bulk to reduce packaging, ugly fruits and vegetables to reduce wastage... We see reborn the working, community and shared gardens and orchards.

The third level of agroecology deals with the relationship between the food system and the society as a whole by taken into account the views, wishes and experiences of the citizens, consumers and practitioners. If agroecology mainly promote alternative ways of productions and distributions, it also an active fight against the conventional methods that contributes to the destruction of our environment, create inequity and unfairness, do not respond to a wise and sustainable use of natural resources. Every citizen should therefore refuse, transform, or even innovate, the proposals made by the experts, whether they are producers, distributors, scientists or politicians. It is on this principle that are formed activists, consumers, neighbourhoods and peasants organisations. For this, agroecology promotes deliberative forums, public debate, dissemination of knowledge and the construction of participatory research mechanisms that guarantee the scientific approaches while taking into consideration the expectations of everyone involved (Stassart et al. 2012).

1.2 What is the social dimension of agroecology?

In a large definition we can use the word “social” as the expression of the relations among the living beings. For instance, certain non-human animals as most of the mammals are called “social species”.

This point helps us to see that the word “social” includes a reflection on what happens among the living beings. We can call it “interrelational perspective”.

From a more anthropological view, the word “social” is more connected to the collective and community dimensions:

How are the groups organised, and how do they work?

What are the people doing when they act together?

What is the difference and the complementarity between acting alone and acting together and when is this balanced or not (we can call this "I/C paradox")?

In the common sense the word “sociality” connects to the word society. This connection explains for example the concept of “social security”, a social warranty that a society gives to their members. It may also connect to a little society: a group of friends, a club, a group of interests (social events, social net…). It connects also with economic, cultural, political, educational and spiritual dimensions of a society.

We have also the concept of social work including several professions working in the social field (working with and for people facing social challenges and social problems).

In the juridical sense, “social” can have ambiguous sense : it can connect to the relations between employers and employees (social lows, social conflicts…) or connect to relations between associates (social mandates).

Practical examples of bio-agriculture experiences

Let’s see in our case how this various social dimensions can be connected and give sense to the agroecological perspective in a degrowth context.

Let’s start our reflexion from 3 concrete cases, the stories of Marcus, of Dorian and Danielle, and of Gerard and Annelies.

Those 3 case stories came from a case study presented in “Agroécologie entre pratique et sciences sociales" (Agroecology between practice and social sciences).4

The presented persons were interviewed two times with a 10 years interval: once around 2001 and once around 2011.

Marcus and the “profitable organisation” perspective

Marcus is born in a farm. He is a 40 years old farmer at the first interview in 2001. He is coming from a large farmer’s family and has several brothers also farmers. One of them is involved in organic farming for several years now and convinced him about the profit he can make with this way of farming. Marcus then decided to shift 20% of his vast fields (350 ha) from “conventional” farming to organic farming (that means 70 ha).He is selling his organic meat and vegetables partly the supermarkets and partly to small distributors, local nets and markets. Business considerations are well present in the first interview. Marcus let us informed for example that he had to separate his farm in two different societies, one for the organic production and one for the conventional production, to avoid administrative problems. His choice for continuing to produce partly in conventional is linked to the opportunity of keeping the interesting quotas he has for producing beets. He is also limiting the working time for collaborators to a half time job (except short time jobbers in the high season). He is using machines in a kind of organic-industry-machines compromise. In the second interview, he is still speaking about business and industry but brings also more ecological considerations such as: quality of food, taste of food, importance that his family can eat with pleasure the farm production. The question of food security and social health is now well present.

Dorian and Danielle : “interaction between ecological and business principles”

Dorian was 40 in 2001 and managed the grand-parents farm (8 Ha) for 15 years. He was first working with a full-time employee in the organic-dynamic perspective. He was producing meat, milk and cereals, and baking bread. He was selling those products on his farm and on several local markets. During the interview, he spoke a lot about his ecological convictions: his concept of an agriculture working with -and not against- nature, about his choice of paying somebody for baking by hand and not with a machine, about keeping a farm at a human dimension, about non growing, about non specializing. He said “I don’t want to do just milk, just bread. The farm is like a living being, it is not only an arm or a leg…”. He preferred that people came to buy directly on the farm.

Because of his convictions, he was acting a little bit differently than his colleagues. He thought it was not useful to calculate too much or to produce mountains of butter. It was enough to do the amount of butter needed “here and now” to make people happy. He liked to take time for those who came to the farm, to show them what he was doing instead of “paying for advertising that will bring very few”…

We find in his speech critical about ecological as well as industrial (not calculating too much) and business (advertising) perspectives.

Ten years later, Dorian met Danielle, his new companion. She developed a cheese production. They are now selling all their products on a real little shop on the farm. They are also selling other products than their own ones: grocery, organic production from other farmers, fair-trade products. Ecological references are thus going on, with this specificity of linking local selling and fair-trade products, of linking local space and Fairtrade…

In 2008, a governmental food agency control detected an inacceptable level of PCB (polychlorobiphenyles) in their milk. They were obliged to stop the milk and cheese production during several months. This was a very difficult episode, financially and morally. They could finally go on thanks to the help, gives and loans of friends and family. This was the time they set up their own little shop on the farm.

Even if they are still critical in 2011 concerning the business, trade and industry principals, once more they still find positive references to its principals. This is especially the case when Dorian explains that after the control they had to find “researches” to “find solutions” (industrial principal). One of those solutions was to organise concerts and meals in the farm. Another initiative was to welcome school classes in the farm. In the more strict agricultural way, they are now thinking how to value the milk or how to keep animals as long as possible, to transform them by themselves and to sell the flesh in their shop in vacuum packing (business and merchant principal).

Gerard and Annelies: from business to social perspective

Gerard is a farmer’s son. At the first interview in 2003, he was 50. He started his career as employee of railway, a job he retrospectively considers as a routine. He decided then to move with his new wife Annelies, a woman who had a sociocultural professional career. They were working with two part-time collaborators on 2.5 hectares. They created an informal association with other producers for a better coordination of their vegetables productions, managing the varieties, quantities and prices. They created together an organic-shop and provided vegetables baskets to the households of the region.

At the time of the second interview, they distanced themselves from this association, preferring to be more deeply engaged in social and ecological aspects with fewer partners. They developed then other activities: bed and breakfast in the farm, collaboration with the village school to train children in organic-agriculture, welcoming young drug-addicts for their social reinsertion. Because Annelies had a life stories techniques training, she proposed individual and collective training to women farmers.

As we can see, ecological and social principles are well present in this case. Compared to the preceding interviews, these principles appears in the option of producing various vegetables on a small scale, of using workmanship more than buying tools and machines and of selling on site. Social and ecological preoccupations have even growth in the second interview in 2011. Distancing themselves with the producers association is justified by the desire to go deeper in sustainable, social and educative activities. When Annelies spoke about life stories, she presents them as a way to help women in rural area to keep a balanced life between the part dedicated to work and the part dedicated to other activities, between what they give to others and what they receive from them.

We can see in those three stories that several principles: agroecological - social -economical - industrial are interacting in different ways.

For a better understanding of those interactions let’s go through the stories with the following exercise.

Proposition of an exercise for looking on a project with the help of 7 criteria

For a better understanding of the social dimension of agroecological examples: organic agriculture, shared gardens, distribution nets, community projects, etc.

Top down (seeds legislation or sanitary controls) or bottom up (initiative of setting up an alternative shop or organising a participative certification net such as Ecovida experience in Brazil) Institutionalisation?

The question of localisation and delimitation: urban or rural area, a countryside where forest and fields are clearly separated or where both are imbricated ….?

Who are the different actors involved or to involve in the project?

What are the collective and/or community dimensions of the project?

A look to the history of a project helps to understand the triple relation between territories, institutions and actors of the project.

What is here the balance between, agroecological, economical, social and industrial dimensions

The exercise aims to share (in little groups) experiences and observations of agroecology, questioning the social dimension of them with those 7 criteria… and/or others.

In a second time you are invited to question the place where we are preparing questions for the inhabitants connected with those 7 criteria.

Content part

2.1 Kick of talk

Ideally this activity is presented by two persons: one should well know the place where the training takes place, the other one should keep in mind the whole program

Aim

Welcoming all the participants of the training and helping them to be comfortable with the schedule (program), living places (presentation of the working, sleeping and eating places) and with the other ones (helping the people to know each other).

Equipment needed and preparation

A room with chairs in circle. A flipchart to note information. Posters with detailed schedule of each day (remaining on the wall all along the training). A paper document with an overview on the schedule for each participant. Eventually, a beemer for presenting pictures of the place, schedule and documents.

Conduct of the activity (one hour)

Quick presentation of each participant (e.g. name and country). A deeper presentation including motivation and competences will be done later during the activity “Why degrowth?”

Presenting the place with all commodities and particularities.

Presenting the main rules of the place.

Overview of the whole schedule with the posters made for each day.

Answering the questions.

2.2. Dance and emotion

Ideally presented by two trainers called here

Aims, consistency with the theme and expectations

Starting training together about “social dimension of agroecology” it’s important that each person first remember “to be present to yourself and to the others as well as of the process of life that is going on through us as persons, collective and community”.

We‘ll go through body and soul exercises that help us and give us a possibility of moving as we feel it and experimenting the feelings and emotions we are going through during this sequence.

Equipment needed and preparations

A large room with a floor allowing dance and body activities, good audio equipment adapted to the size of the group (between 15 and 30 people). A lighting that can be very bright or more discrete depending of the different moments of the activity. A number of 1m long sticks (one by participant). Each participant has to wear clothes that allowed free movement.

Conduct of the activity (60-90 minutes)

- Walking …. Slowly…. very slow …. Little bit quicker, quick, quicker ……and coming back to slower, slow and very slow. Danou

Presence to yourself…. Space …. Changing direction - Group awareness

Breathing - opening myself to my breath, getting deeper and slower, feeling what happens all along the breathing canal from noise and mouth to the deepest inside of the body. Breathing helps to feel! Air and voice: voice games – collective improvisation: voicing helps to express. Rhythms a connecting between the people. Rhythm, voice and movement help to feel a vital energy, a feeling of life. François

Sticks - let’s form two groups: the first is acting and the second is looking and observing what happens.

Playing with the sticks by pairs: A is the leader - B follows … or not…

Nobody is the leader - B is the leader

Games by 3 persons-groups

If there is some more time: games with wire Danou

Free sequence Games with feet and percussions Danou

Various Geometry…: following my own hand - first alone, than in groups of 2, 3, 4... until 6 !

Dances by six without touching each other but being connected! Danou

Big double circle - everybody looking to the inside of the circle. Feel and find yourself again after all those games. Closing the eyes and breathe again deeply and slowly.

Than each participant from inside are doing little steps to the left side during a certain time… then stop. Slowly the people in outside circle, keeping closed eyes, present their two hands with the palms up. The people in the inside circle let progressively their hands come into the hands of the other without forcing something. Each one contacts and encounters the other with respect. Be attentive to what is experienced and felt. François

Examples of outcomes

Better conscience of breathing in the immobility as in the movement allowing a better contact with oneself.

Discover of the pleasure of free voicing together connected with the pleasure of cooperation.

Discover of the necessary nuances in the interactions for having a good collective result trough the sticks game.

Experiencing different kinds of rhythms and the possibilities of harmonising them.

Experiencing emotions with other participants and exploring with them the possibility of expressing feelings and sensations after those experiences. (all dance games and especially the exercise with hands at the end).

How to evaluate ?

Have a precise observation of each participant and of the whole group dynamic during the activity. Look how people are entering and engaged in the activity.

At the end of the activity, all participants sit in circle. Then ask each of them to say a little word or a little sentence that express what he was experiencing during this activity.

. What is degrowth? – a role-play

Aims, consistency with the theme and expectations

The purpose of the role-play is to enable participants to realise that:

- there are a lot of arguments in favour of degrowth;

- that degrowth takes place at various levels (economic, social, political, scientific, educational, local ...)

- that the various actors involved in degrowth can have different or even contradictory motivation

It also aims to teach participants how to defend their own convictions, while remaining open-minded to the convictions of the others. So they are placed in a situation where they have to argue the conviction of a category of the population with particular interests.

Because the defenders of degrowth are often passionate people, their speech can sometimes seem radical or sanctimonious. This role-play aims to teach them to be more responsive to others and less moralistic.

Equipment needed and preparations

A room where participants can meet in small subgroups of 4 to 5 people.

Labels on which are written the name of a particular category of the population: scientist, politician, economist, citizen, artist …

One envelops for each subgroup with a single representative of each population category on labels.

Conduct of the activity

At first, a short presentation is given to remind participants why degrowth is needed for the survival of the human being and why our present western way of life is no longer sustainable without digging deeper in the social and economic gap that separates us from the rest of the world. The presentation can be found here.

Then, the facilitator gives the instructions of the role-play:

form groups of 4 to 5 people

each group receive an envelope with labels

each people picks a label in the envelope and must play the role indicate on the label

the role-play lasts 30 minutes during which each people has 5 minutes to argue why his character (scientist, artist, economist, activist, …) is the most important one to defend and promote degrowth.

How to evaluate ?

Main arguments for each character can be summarised on a flipchart. Meanwhile, the facilitator must not forget that the aim of the role-play is not really to find argument but learning to combine with the views of the others.

2.4. Discovery of the social life at the farm “Vévy Wéron” part I

Aims, consistency with the theme and expectations

The main objective of this activity is to explore the social structure of the inhabitants of the farm Vévy Wéron. Through this activity, it’s attended to understand not only its current structure, but also how it emerged over time. It also aims to collect the motivations (philosophical, economical, societal...) of families to settle there, the incentives and disincentives of such a lifestyle, how they are selected and how they are integrated by the other families.

These aims are consistent with the theme of degrowth because they are related to the concepts of solidarity and sharing, of voluntary simplicity and resilience, and of environmental care and health.

Solidarity and sharing are mainly expressed in the social lifestyle of the farm. Voluntary simplicity is a personal matter. Environmental care and health are meanly assessed through the farming and food production activities.

Equipment needed and preparations

You need a room for the first part of the activities where participants can sit in a circle.

Participants should dress work clothing for an outdoor walk.

Conduct of the activity

A representative of farm residents is introduced in the room. For an hour, he exposes the history and rules of life of the farm. As he wished, he answers questions from participants during his presentation or at the end.

After a small break where participants are asked to dress with warm clothes, they are divided in subgroups of less than 10 people each for a guided tour of the farm. Voluntary inhabitants of the farm that are sufficiently fluent in English guide the subgroups for the tour. The maximum number of participants for each subgroup must not be too high in order to keep the tour convivial, not to afraid the guide (he’s not a professional guide), and to allow everyone to ask questions without being too oppressive for the guide.

Because each guide is an inhabitant of the farm with his own past, motivation and centre of interest, each tour is unique. As a result, after the guided tour, participants are invited during the teatime to share their experiences. Participants must also keep in mind that the information they collect from the guide will be use later in the TTT exercises.

2.5. Evening conference debate around the themes of degrowth and education

Aims, consistency with the theme and expectations

The goal of the first part of the conference debate evening is to remind the history and main foundations of the philosophy of degrowth through presentation given by a subject matter expert.

In a second part, as part of the “training the trainers” objectives, the participants are initiated to the guidance of a philosophy café oriented to the theme “degrowth and education”. The aim of this second part is to learn a technique of debate guidance were participants are asked to propose and debate solutions to a specific problem in a serene atmosphere that promotes innovations, critical thinking and collaboration.

It is expected from the participant to realise that the future trainer is not supposed to be an expert in degrowth. Nobody is supposed to be an “absolute” expert in all the action areas regarding degrowth (energy, pollution, mobility, gardening, recycling …). The role of the trainer is not to provide knowledge, he may if he can, but his main role is to manage the debates in order to make the participants aware of their own abilities to:

find solutions by themselves ;

find solutions thanks to the group, thanks to the sharing of resources and experiences ;

realise that there is not only one good solution, a unique way to get involved in degrowth.

Equipment needed and preparations

Time laps: 2 hours.

A room where participants can sit in a circle.

A flipchart or a blackboard and writing material.

A small paper sheet and a pencil for each participant.

Conduct of the activity

Part 1: conference

Time laps: 1 hour.

Part 2: philosophy café

Time laps: 1 hour.

The facilitator of the philosophy café gives a small sheet of paper and a pencil to each participant and asked him to write an answer to the question that will be asked. The answer must be short, as a single sentence, and personal. In our exercise, the question was “Which education for tomorrow's society in a context of degrowth?”

The answers are collected in a bag and given to the facilitator who randomly picks one in the bag and reads aloud. If needed, he may ask the writer for clarification.

Participants may intervene to argue the reasons for their approval or disapproval regarding the proposed solution. Participants who wish to speak should raise their hands. The facilitator distributes speech to allow everyone to express himself or herself.

When there is no more comment or after a while, the facilitator picks a new answer in the bag. In one hour, it is expected to consider 4 or 5 answers, no more.

During the last 10 minutes of the activity, the participants are asked to summarise the debate through a single word they loudly tell at the audience. Then, they can vote for the best word.

At the end, the facilitator summarizes the methodology so that participants are well aware of the procedure, the objectives and the role of the facilitator.

How to evaluate ?

- Were the participants loquacious, talkative ?

- Was each participant able to speak at least once?

-Did the chosen concepts stimulate the reflexion ?

- Does the final word satisfy everyone?

Examples of outcomes

No outcomes are expected because this philosophy café is just an exercise. But as a tool, the philosophy café is a good way to make people collaborate in finding solutions to simple problems.

2.6. Discovery of the social life at the farm “Vévy Wéron”

Aims, consistency with the theme and expectations

The main objective of this activity is to live part of the inhabitant’s everyday life at the farm Vévy Wéron. It aims to understand that community living offers many advantages but also involves obligations.

A secondary objective is to learn a technique or practice that is both related to degrowth and related social life in the farm.

Equipment needed and preparations

Well in advance, you need to negotiate with the inhabitants of the farm a list of workshop to be proposed to the participants, and the maximum number of participants for each workshop. So, inhabitants have the time to schedule the workshop and to prepare the needed tools and material.

You need a room with a flipchart.

Participants should dress work clothing for outdoor work such as gardening.

Conduct of the activity

Participants register on a flipchart on which several outdoor or indoor workshops are listed. The maximum number of participants for each workshop is indicated on the flipchart.

The proposed workshops are manual works directed by the inhabitants of the farm and that are part of their normal work. It’s supposed to last two hours. In our course, the manual works were the followings:

To cut and dry nettles for feeding the donkeys.

To prepare the evening vegan meal with the cooker.

To prepare apple pies for the teatime.

To store wood for winter.

To build a wooden crate for composting pit toilet wastes.

To manufacture a puppet booth.

To help milking the goats.

To sort the apples in crates.

To help at the bakery.

During the workshop, the participants are expected to learn the technique, to understand its usefulness and its place in the life of the farm, and to understand how it fits in a degrowth process and agroecology. At the same time, they can continue the discussion with the inhabitants.

After the workshops, participants and inhabitants are invited the have a common teatime and diner during which everyone can share and compare their experience in a friendly atmosphere.

How to evaluate ?

- Are the discussions at the teatime or diner focused on – or enough connected to- the experiences lived by the participants during the workshops?

-What were the most deepened subjects in the discussions ?

- Are participants satisfied with their work?

- Do they exchange experiences among them or with the inhabitants?

2.7. Visit of the farm “Nos Pilifs”

Aims, consistency with the theme and expectations

- Presentation of a sheltered workshop for disabled people.

- Learning how a commercial company located in urban areas is concerned with the protection of the environment and how it is involved in agroecology.

- Show how to combine agroecology and social integration of disabled people.

Equipment needed and preparations

Here, we took contact with the farm well in advance in order to schedule our visit. The visit includes a presentation of the farm in a seminar room with a film and slides, a tour of the infrastructures guided with team leaders, and a vegetarian lunch prepared by disabled workers with organic or local food.

Participants should dress clothing for outdoor walk.

Conduct of the activity

Part 1 (one hour)

The general presentation of the farm is give through a film and slides in a seminar room equipped with the required video material. The film is available here (part I) and here (part II). A translation of the film is proposed here. The translation is loudly given simultaneously with the film.

The slide presentation about the place of agroecology at the farm is given here.

The participants are invited to ask questions at the end of the presentation but the questions session must be short. The participants are indeed told they may continue to ask questions during the guided farm tour.

Coffee and tea are offered before leaving the seminar room.

Part 2 (one hour)

The participants are divided into two or three subgroups for more conviviality. They are guided through the different buildings and farm workstations. They can meet and discuss with the workers. The guide focuses his speech on agroecology, recycling, energy and water saving, and on the social integration of disabled people.

Part 3 (one hour and a half)

Nos Pilifs farm has a tavern where a room has been especially reserved for the participants. A vegetarian dish has previously been ordered. As every workstation of the farm, the dish at the tavern is prepared by disabled workers and is made of organic or local food.

How to evaluate ?

-Did the participants understand “What is done here ?”

-Did the participants have enough time and information to understand the constraints of such a company that must combine profitability, environmental concerns and integration of people with disabilities?

-Do they have time to discuss the choices made by the company and consider other solutions?

-How were the interactions after the film, during the visits, during the discussions, during the diner?

-Did they identify this experience as a work on “social dimension of agroecology” ?

2.8. Visit of Haren district and encounter with the “patatist activists”

Aims, consistency with the theme and expectations

Have a focus on the political dimension of agro-ecology. See how alternative projects bring lot of links between the participants creating a strong social dimension in those projects. Discover of different dimensions of political engagements (from “just a new little idea, simply different” to “hard activist movement” through agroecological projects.

Equipment needed and preparations

Taking contact with different people managing projects in this District: Evere urban farm, Haren Gardeners, Cultural center of Haren “De Linde”, Patatist representatives.

Participants should dress clothing for outdoor walk.

Beamer and documents ready for presentation in the cultural center.

Conduct of the activity (half a day – here from 14:00 to 22:00)

Travelling from Nos Pilifs to Evere urban farm - 30 min

Visiting the Evere urban farm with Thomas, farmer-trainer in the project - 45 min

Debriefing of the visit in Circle - 15 min

Travelling from Evere to Haren - 30 min

Visiting the district of Haren guided by Haren urban gardeners and inhabitants, discussing with them about the agroecological state of the district on the way to the Kelbeek - 60 min

Encounter with patatists in the Kelbeek and visiting the infrastructures built on the place where the construction of a mega prison is planned. - 30 min

Discussion with them in the tent: Who are the patatists? - Story of the movement from the first day where they planted potatoes in this field (april 2014) with 400 persons until today (November 2014) with the construction of more permanent infrastructures for occupying the place – Who are the persons engaged in this movement and how do they live? -what is the impact of the movement on the political authorities responsible for the prison project? - Connection between patatists and the movements “Campesina” and “Landless peasants”? – What is the future of the movement ?

All this discussion is happening in a circle with a facilitator helping for questions and answers, exchanges of ideas and debates to be done in a respectful and open mind perspective - 60 min

Travelling to Haren cultural center “De Linde” for a conference by Elisabeth Grimmer (Inhabitant of Haren) aiming to synthesize all the problematic of the project “Prison of Haren” including a discussion with the audience (participants of Growl training and some other participants invited) - 60 min

Buffet – Dinner allowing easy exchanges between participants - 60 min

Travelling to the sleeping place (here at the Haute Ecole de Bruxelles) - 60min

Outcomes

Discover of agroecological projects on a concrete way by visiting them on the field and encountering the people who are in the center of the action.

Awareness of the tension lived by the Haren inhabitants between the gardening tradition they have and the planned mega-project.

Encounter with Haren inhabitants through discussions, visiting their district and sharing a meal with them.

Experimenting the core of an activist movement and looking on their motivations, engagement and modes of action.

How to evaluate ?

-Did we have a good time management to have an interesting look on the several projects?

-Was this succession of visits good balanced between “adventure and comfort”?

-How were the interactions during the visits, during the discussions, during the conference, during the diner?

-Is the problematic of Haren clear in the mind of the participants?

2.9. Training the Trainers (TTT) – I – World café

Introduction

At the early beginning of the course, participants were given the “Train-the-Trainer module” document (available here). A short presentation of the document is given. People are told that they can use the back of the sheets to take notes during the activities. They are also told that their notes will be very important for the TTT day.

Aims, consistency with the theme and expectations

The main objective of this world café is to allow each participant to be aware about the different elements that should be taken into account when preparing its own activity. This awareness is done through three analysis grids: analysis of the key levers and obstacles; analysis of the environmental issues; analysis of the global brain.

The analysis grid of the key levers and issues consists of a series of questions to ask oneself to properly prepare its activity.

- For my project, which educational methods?

- People involvement?

- Practical scenarios in learning?

- Citizen-based approaches?

- What is the motivation of the people?

- Which support from the management and from de colleagues?

- Which partnerships with other organisations?

- How much time is dedicated to coordination?

- Which material and financial supports?

- Which support from referees and/or from people from the outside?

- Which communication means?

- Which consistency?

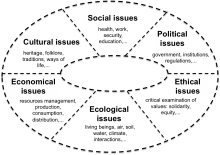

The Environmental issues analysis grid aims to allow the trainer to be aware that there are many fields of action or target audiences, or to ensure that all fields of action and target audiences are taken into account by the training. These fields of action or target audiences are the followings:

The global brain analysis grid aims to allow the trainer to be aware that people think and learn in different way. Some parts of the brain dominate the others, and therefore people are more receptive to certain arguments or sensitive to certain approaches.

There are four main types of brain, depending on what they value most (more information here – in French):

INFORMATION I value knowledge | IMAGINATION I value intuition |

EXPERIENCE I value practical action | FEELINGS I value sensitivity |

People who value knowledge are used to understand and learn thanks to simple oral or visual presentations (lectures, courses, books, demonstration, visits...).

People who value intuition perform in creative workshops where they are free to create and imagine.

People who value practical action do not just need to see or to ear but they must also practice to learn. Cooking, building a wooden crate for composting pit toilet wastes, manufacturing a puppet booth… are such practical activity we organised.

People who value sensitivity need to touch thinks or to share with the others in a convivial atmosphere to live and to feel emotions. They mostly learn and memorise when things are full of emotions. Petting goats, listen to a moving testimony, having fun at teatime, shearing meal of cooking together are such activities that can bring emotions.

Equipment needed and preparations

A large seminar room where subgroups of 4 to 5 people can sit at round tables.

Large sheets of paper and colour pencils.

Adhesive gum or tacks to hang paper sheets on the room's wall.

Conduct of the activity

Part 1 (half an hour): levers and obstacles

People are invited to sit at round tables in subgroups of 4 to 5 people. A large sheet of paper is given for each table. The sheet is previously divided in two columns (levers on the left side – obstacles on the right side) and shows a central label with the title “Projects or places visited”.

People are invited to fill both columns of the sheet with what they consider as levers or obstacles to a single or the whole projects and places visited during the past few days. They can fill it by their own way: with words, short sentences, drawings...

At the end, all the sheets are fixed on the room’s wall and people are invited to browse all the sheets. The aim of the display is to find the important items and synthesise them.

As an alternative to the display of sheets, a person may be designated as spokesman of the table. For the following analysis grid, all the people are changing table, except the spokesman. The latter then made a report to new members of what has been done by his group. A discussion can then take place in order to find the important items and synthesise them. A new spokesperson is then nominated for the next analysis grid.

Part 2(half an hour): environmental analysis grid

Same methodology than part 1. The environmental issues analysis grid is stuck in the centre of the sheet and the pie areas of the grid are extended by lines to the edges of the sheet. The theme of the grid (here “agroecology”) is written in the central circle of the grid. In our exercise, the participants have to fill in the pie areas in order to answer the following question: “What have we done, see, or learned about agroecology during our course that could be related with the different issues mentioned on the grid?”. The answers could deal with activities, feelings, concepts, people, methodology…

Part 3 (half an hour): global brain

Same methodology than part 1. A symbol evocating the brain is stuck in the centre of the sheet. The sheet is divided in for quarters that represent the four types of the global brain. In our exercise, the participants have to fill in the quarters with the activities of the week that mostly fit with one of the four categories of the grid.

Examples of outcomes

Here are examples of outcomes from the three grids.

Part 1: example of levers and obstacles analysis grid

Part 2: example of environmental analysis grid

Part 3: example of global brain analysis grid

How to evaluate?

Analysis grids can be used both for preparing and evaluating the activities. When preparing and filled in by the trainer, it can warn him that some dimensions or target audiences are not taken into account. At the end of the course (or activity), it can be filled in by the participants of the training as an evaluation tools for themselves and for the trainer.

2.10. Training the Trainers (TTT) II “Be in the trainer position”

In the end of this training, as an “open conclusion” participants are invited to choose individually and to discuss in little groups of 3 – 4 persons a subject they would like to present in the position of the trainer (individually or in binomes…). This theme can be choosed in the different subjects already presented this week or can be a new subject (connected with the week theme “social dimension of agroecology”).

The focus is double:

- on the content of the presentation (what’s about?)

- on the methodology: what is the form of the training (presentation, game, interactive exercise, art performance…)?

This group work will be a starter for developing ideas by participants and help them to take the position of trainer in their own contexts.

At the end of this sequence, we can experiment one or two proposed trainings in the form of micro trainings (15 min activity – 15 min debriefing).

References

Altieri, MA 1987, Agroecology: the scientific basis of alternative agriculture. Westview Press, Boulder, CO, USA.

Biesmeijer, JC, SPM Roberts, M Reemer, R Ohlemüller, M Edwards, T Peeters, AP Schaffers, SG Potts, R Kleukers, CD Thomas, J Settele & WE Kunin 2006, “Parallel declines in pollinators and insect-pollinated plants in Britain and the Netherlands”, Science, vol. 313, no. 5785, pp. 351-354.

Francis, R, G Lieblein, S Gliessman, TA Breland, N Creamer, R Harwood, L Salomonsson, J Helenius, D Rickerl, R Salvador, M Wiedenhoeft, S Simmons, P Allen, M Altieri, C Flora & R Poincelot 2003, “Agroecology the ecology of food systems”, Journal of Sustainable Agriculture, vol. 22, no. 3; pp. 99-118.

Gliessman, S 1998, Agroecology: ecological Processes in Sustainable Agriculture, Chelsea, MI: Ann Arbor Press.

Kevan, PG & TP Phillips 2001, “The economic impacts of pollinator declines: an approach to assessing the consequences”, Ecology and Society, vol. 5, no. 1, p. 8, [online] URL: http://www.consecol.org/vol5/iss1/art8/

Perfecto, I & J Vandermeer 2010, “The agroecological matrix as alternative to the land sparing/agriculture intensification model”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 107, no. 13, pp. 5786-5791.

Potts, SG, JC Biesmeijer, C Kremen, P Neumann, O Scheiger & WE Kunin 2010, “Global pollinator declines: trends, impacts and drivers”, Trends in Ecology & Evolution, vol. 25, no. 6, pp. 345-353.

Stassart, PM, P Baret, J-C Grégoire, T Hance, M Mormont, D Reheul, D Stilmant, G Vanloqueren & M Visser 2012, “L'agroécologie : trajectoire et potentiel pour une transition vers des systèmes alimentaires durables”, pp. 25-51 in Van Dam, D, M Streith, J Nizet & PM Stassart, Agroécologie entre pratiques et sciences sociales, Educagri Editions, Dijon.

Summer, DA & H Boriss 2006, “Bee-economics and the leap in pollination fees”, Agricultural and Ressource Economics Update, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 8-11.

1 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ecology - 10.IV.2015

2 Cited by Stassart et al., 2012.

4Denise Van Dam and Jean Nizet In Agroecologie entre pratique et sciences sociales pp 249-264 Ed Educagri

- 1455 reads